Purple Prose:

conflict

Your Characters’ Humor

Promises Promises Promises

On My Writerly Bookshelf

Writing Kickass Action Scenes: Part Three

Writing Kickass Action Scenes: Part Two

Writing Kickass Action Scenes: Part One

Adding Dimension

What the @#*!? (or Dealing with Critiques)

Page Turners in Romance (YA and adult)

Emotional Conflict

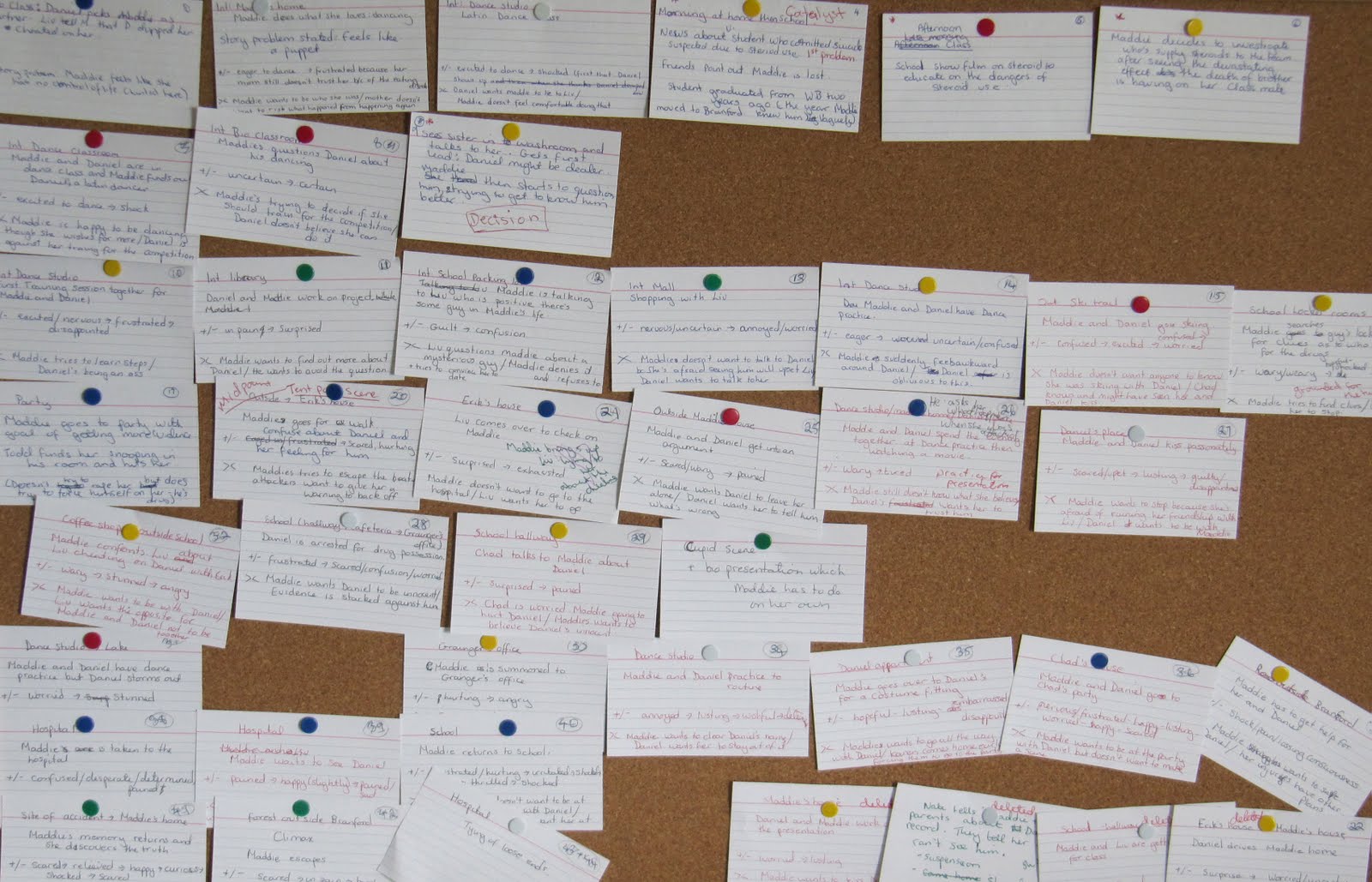

Get Corked: The Screenwriters’ Trick for Plotting

Realizing Your Characters’ Fears

Enriching Your Story

Querying Paralysis

On My Writerly Bookshelf

Setting in Conflict