Purple Prose:

riveting words

What Anne Geddes Taught Me . . .

The Twenty-Minute Workout (for your MS)

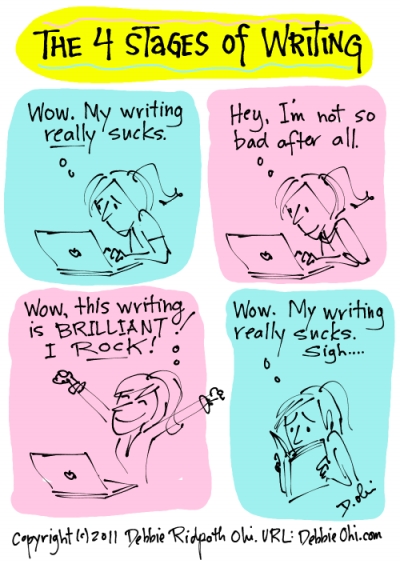

Becoming a Kickass Writer

First Line. Last Line

Don’t Do As They Do

Evoking Emotions in Your Descriptions

Abusing Those Poor Idioms

Those Tricky Little Idioms

Doing the Impossible

Leaping Back in Time (part 2)

Leaping Back in Time (part 1)

Clichés, Subtext, POV, Oh my!

Body Part Workout

The Thesaurus Extraordinaire

Don’t Leave ’Em Dangling

Get active!

Oh Me Oh Mi of Overwriting

The Mysterious Voice

Riveting First Words