Purple Prose:

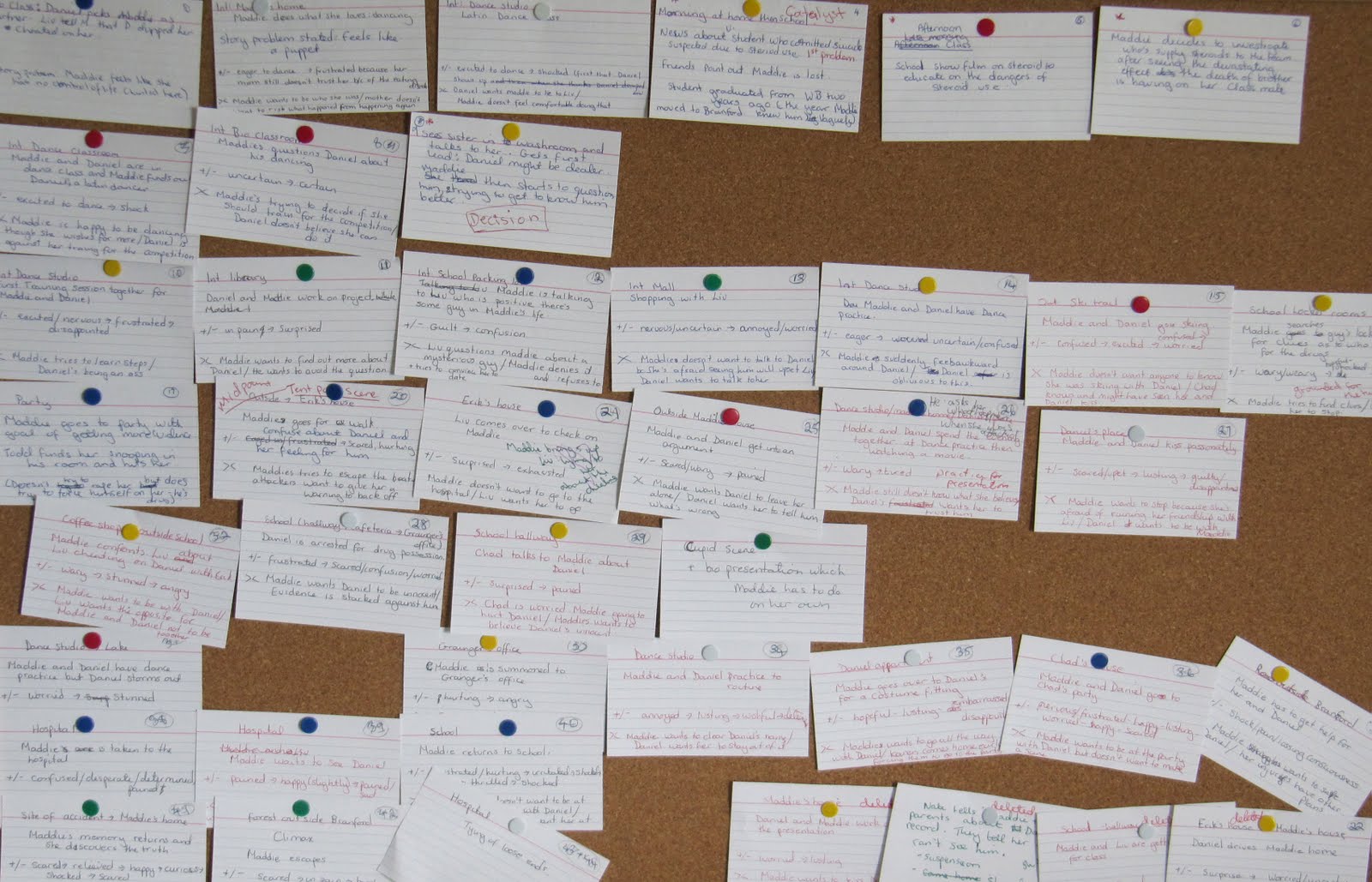

plotting

One, Two, Three to Analyzing Great Stories

Keep it Simple

Plots and Hooks, Think Symphony!

Expanding Beyond Your Genre (and meet Brad Pitt)

The Twelve Days of Christmas for Writers: Day Eight

Get Corked: The Screenwriters’ Trick for Plotting

The Emotional Structure of Tangled: Part Two

The Emotional Structure of Tangled: Part One

The Twenty-Minute Workout (for your MS)

On My Writerly Bookshelf—and exercise

On My Writerly Bookshelf

On My Writerly Bookshelf

Enriching Your Story

Researching Believability

Q & A with Joanna Volpe

It's All in the Preparation